Now Reading: Patan Durbar Square: Where Dynasties Rose, Fell, and Still Whisper Through Brick and Stone

-

01

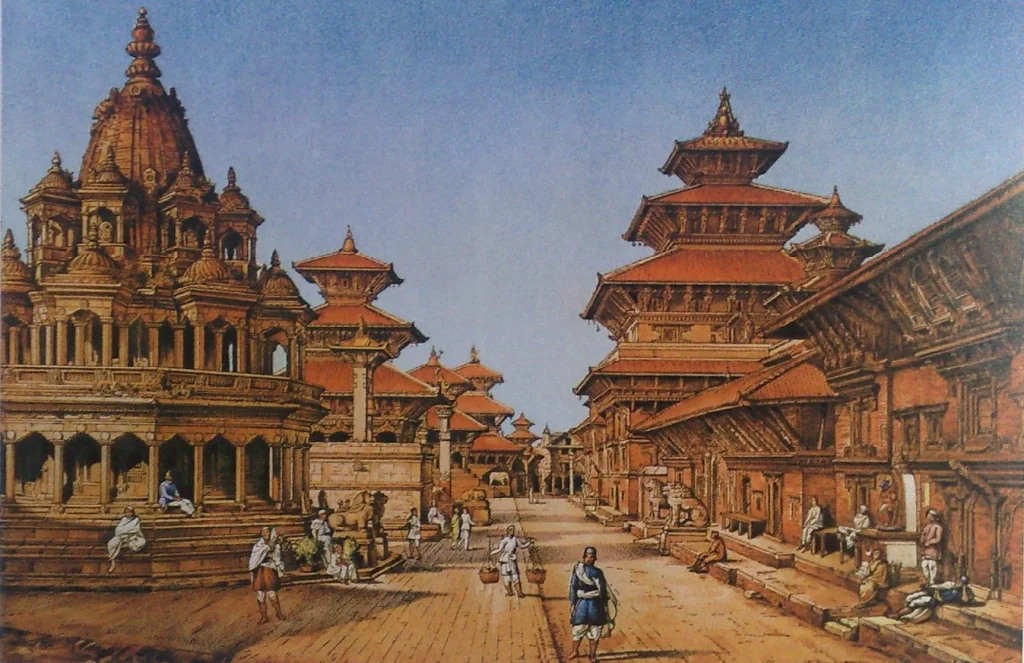

Patan Durbar Square: Where Dynasties Rose, Fell, and Still Whisper Through Brick and Stone

Patan Durbar Square: Where Dynasties Rose, Fell, and Still Whisper Through Brick and Stone

There are places in Nepal that you pass through quickly.

And then there are places that slow you down without asking permission.

Patan Durbar Square, in the ancient city of Lalitpur, is not simply a historic plaza of temples and palaces. It is a layered chronicle of power, devotion, artistry, conquest, resilience, and everyday life. It is where the Newar civilisation reached extraordinary refinement. It is where Malla kings ruled with ritual authority. It is where the Shah dynasty absorbed a kingdom into a unified Nepal. And it is where, even today, butter lamps flicker as they have for centuries.

When you walk into the square, you do not just see monuments.

You feel continuity.

Recommended Read: UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Nepal: Complete Guide to All 10 Cultural & Natural Treasures

A City Older Than Its Written History

Patan, historically called Lalitpur, meaning “City of Beauty,” is believed to be one of the oldest cities in the Kathmandu Valley. Archaeological evidence and local tradition suggest settlement dating back more than two millennia. While the earliest political records are fragmentary, the city’s spiritual landscape hints at deep antiquity.

Legend connects Patan to Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan Empire in the 3rd century BCE. It is said that he built four stupas at the cardinal points of the city. Whether historically precise or not, the presence of these ancient stupas suggests that Patan was already a significant Buddhist centre long before the medieval period.

By the Licchavi era, between the 4th and 9th centuries, the valley had developed into a structured polity with inscriptions, temple foundations, and trade networks extending toward India and Tibet. But it was later, during the Malla period, that Patan would crystallise into the architectural masterpiece we experience today.

Unlike cities shaped by rapid expansion, Patan evolved deliberately. Its urban planning followed mandala principles rooted in Hindu and Buddhist cosmology. The square was not simply administrative space. It was cosmological space. It represented a microcosm of order, power, and divine presence.

When you stand in the square now, surrounded by layered brick facades, it feels as though the city grew not outward, but inward.

The Malla Golden Age: Refinement as Statecraft

Between the 12th and 18th centuries, the Malla dynasty governed the Kathmandu Valley through three rival kingdoms: Kantipur, Bhaktapur, and Patan. Competition among them was intense, but it was not always military. Often it was artistic.

In Patan, kings such as Siddhi Narasimha Malla in the 17th century turned patronage of art into a form of political expression. Temples were built not merely for worship, but as declarations of sophistication and legitimacy.

Krishna Mandir was constructed in 1637. Palace courtyards were expanded. Ornamental windows were commissioned with astonishing intricacy. Metal casters produced bronze icons that would travel far beyond Nepal’s borders.

The Malla kings practised both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, often simultaneously. Royal rituals incorporated tantric elements. Goddess worship was central. The royal palace was not only a residence but also a sacred arena where divine favour was invoked to legitimise earthly rule.

Art here was never decoration.

It was governance in carved form.

Walk slowly across the square and look at the wooden struts beneath the temple roofs. Many depict powerful deities in dynamic, even fierce, poses. These were not random images. They signified protection, cosmic order, and royal authority.

Patan during the Malla era was not simply prosperous. It was intellectually and spiritually vibrant. Scholars, priests, artists, and merchants created a culture of layered sophistication that still defines the city.

Krishna Mandir: Stone Narrative of a Kingdom

At the heart of the square stands Krishna Mandir, a temple unlike any other in the valley.

Built entirely of stone, inspired by North Indian shikhara architecture, it breaks from the traditional pagoda style dominant in Nepal. Commissioned by Siddhi Narasimha Malla, the temple rises in elegant tiers crowned by twenty-one golden pinnacles.

Its structure is deliberate. Each level corresponds to sacred symbolism. The ground level houses images from the Mahabharata. The middle level references the Ramayana. The upper sanctum is dedicated to Krishna himself.

Run your fingers gently across the stone carvings, and you feel the discipline of artisans who carved epic narratives into rock. Warriors ride chariots. Divine battles unfold. Scenes of devotion appear in miniature panels.

During Krishna Janmashtami, the temple transforms completely. Thousands gather. Oil lamps illuminate every contour. Devotional songs ripple outward through the square. For a moment, the 17th century feels present.

Krishna Mandir was more than a temple. It was a statement.

It declared that Patan could rival any kingdom in artistic grandeur.

The Royal Palace Complex: Architecture of Authority

Opposite the Krishna Mandir stretches the royal palace complex, once the administrative and ceremonial heart of the Malla kingdom of Patan.

This is not a singular palace. It is a network of courtyards, halls, and shrines, each with layered meaning.

Mul Chowk functioned as the primary ceremonial courtyard. Here, royal rituals and state ceremonies took place. The layout reflects tantric symbolism, with Taleju, the royal goddess, occupying a central sacred position.

Sundari Chowk is perhaps the most refined of all. At its centre lies Tusha Hiti, a sunken water reservoir adorned with exquisite stone carvings. The spout features intricate iconography representing Vishnu in a subtle, meditative form. The courtyard’s intimacy contrasts with the public grandeur of the main square.

These courtyards were not merely aesthetic achievements. They reinforced hierarchy, sacred power, and controlled access.

When the Shah dynasty conquered the valley in the 18th century, this palace ceased to be the seat of sovereign authority. Yet it did not lose its cultural gravity. Today, it houses the Patan Museum, preserving bronze sculptures and ritual objects that once animated these spaces.

The palace shifted from political centre to cultural archive.

But the stones still remember the ceremony.

The Shah Conquest: Unification and Transformation

By the mid 18th century, the political landscape of Nepal was fragmented. Prithvi Narayan Shah, king of the small hill state of Gorkha, envisioned a unified kingdom.

After years of strategic blockades and military campaigns, he captured Kantipur in 1768. Patan soon fell under Shah control.

For Patan, this marked the end of independent Malla rule.

Unlike a destructive invasion, the Shah takeover was strategic and calculated. Administrative systems were absorbed rather than dismantled. Religious institutions were preserved. Local elites were integrated into the new political order.

The Shah dynasty chose Kathmandu as the primary capital. This shifted political gravity away from Patan’s palace complex. The square transformed from a sovereign royal centre to part of a unified national structure.

Yet the cultural framework of Patan remained remarkably intact.

Newar festivals continued. Temple rituals persisted. Artisans maintained their workshops.

The conquest altered political authority but did not erase identity.

Standing in the square today, you sense both rupture and continuity. The echoes of Malla sovereignty linger in architecture. The shadow of Shah unification lingers in national memory.

Patan did not resist history.

It absorbed it.

Taleju Temple: Sacred Kingship Beyond Dynasties

The Taleju Temple symbolises divine kingship. For the Malla rulers, Taleju Bhawani was the tutelary deity whose blessing legitimised their reign.

Access was restricted. Rituals were elaborate. Kingship was understood as a sacred duty, intertwined with tantric worship.

After the Shah conquest, the temple retained its sanctity. Even as political power shifted, the spiritual aura of Taleju endured.

During special festivals, the temple opens briefly. Devotees line up quietly. The air feels charged.

This continuity reflects something deeper about Patan. Dynasties may fall, but sacred geography persists.

Bhimsen Temple and the Merchant Spirit

The Bhimsen Temple represents another dimension of Patan’s identity.

Bhimsen, revered as a deity of strength and trade, reflects the city’s mercantile roots. Newar merchants historically travelled along trans Himalayan trade routes connecting Tibet and India. Wealth from commerce fueled artistic patronage.

The temple’s wooden façade features finely carved windows and struts. It watches over the square as a reminder that economic vitality supported cultural brilliance.

Even after political unification under the Shahs, Patan’s artisanal economy continued to thrive.

Today, metal workshops near the square still produce bronze statues using techniques refined during the Malla era.

Craft is continuity.

Festivals, Rituals, and Living Heritage

What distinguishes Patan Durbar Square is that it has never become static.

The Rato Machhindranath chariot festival remains one of the longest and most elaborate festivals in Nepal. The towering chariot moves slowly through Lalitpur’s streets, accompanied by music, ritual chanting, and communal participation.

Indra Jatra, Gunla, Bisket, and countless smaller rituals animate the square throughout the year.

Children play on temple steps. Elders gather in quiet conversation. Devotees circle shrines in the early morning.

This is not heritage curated for display.

It is a heritage embedded in daily rhythm.

Earthquake and Restoration: The Test of Time

In 2015, the earthquake damaged several structures in Patan Durbar Square. Temples collapsed. Roofs cracked. Ancient beams splintered.

Yet restoration efforts began swiftly.

Local craftsmen, many descended from traditional artisan lineages, led reconstruction using age-old methods. Brick by brick, beam by beam, the square was revived.

This was not mere rebuilding.

It was reaffirmation.

Patan has survived dynastic change, political transformation, colonial intrigue, natural disaster, and modernisation.

And still, at dusk, the bells ring.

Why Patan Feels Intimate

Kathmandu’s royal square feels monumental. Bhaktapur feels expansive and medieval.

Patan feels inward.

The scale invites attention. The details reward patience. The courtyards feel contemplative rather than grandiose.

Knowing that this square witnessed the splendour of the Mallas and the strategic consolidation of the Shahs deepens the experience.

You are not just walking through architecture.

You are walking through a conversation between dynasties.

Walking Away With History Under Your Skin

As evening descends, Krishna Mandir’s stone softens in fading light. The palace walls glow amber. Butter lamps flicker in alcoves.

You sit for a moment.

This square has witnessed coronations, tantric rituals, conquest, unification, restoration, and renewal.

And yet it does not feel burdened by history.

It feels alive.

When you finally step away into the narrow lanes of Lalitpur, you carry more than images.

You carry the understanding that Patan Durbar Square is not just about the past.

It is about endurance.

It is about culture that adapts without dissolving.

It is about a city that absorbed conquest, honoured its traditions, and continues to breathe through brick, stone, and prayer.

And that is why it stays with you.