Now Reading: From Bells at Dawn to Fires at Dusk: A Full Day Inside a Nepali Village

-

01

From Bells at Dawn to Fires at Dusk: A Full Day Inside a Nepali Village

From Bells at Dawn to Fires at Dusk: A Full Day Inside a Nepali Village

A day in a Nepali village does not announce itself loudly. It unfolds, patiently, rhythmically, guided by light, weather, and habit rather than clocks or schedules. From the first sound of temple bells at dawn to the quiet glow of kitchen fires at night, village life moves with a steadiness that feels both ancient and deeply human.

For travellers who spend even a single full day in a Nepali village, time begins to feel different. Slower, yes, but also fuller.

Dawn: When the village wakes gently

Before the sun rises above the hills, the village is already stirring.

A bell rings from a small temple somewhere uphill, its sound drifting across fields and rooftops. Roosters answer in a confident chorus. Smoke curls upward from one or two early kitchens where water is being boiled for tea. The air is cool, fresh, and unmistakably alive.

Elders wake first. Wrapped in shawls, they step outside to sit on stone steps or low wooden benches, warming their hands around cups of chiya, sweet milk tea laced with ginger or cardamom. There is little conversation. Morning is for presence, not performance.

For visitors staying in homestays, this moment often feels sacred. You are not observing village life; you are quietly included in it.

Morning rituals: Work, prayer, and shared space

As light fills the valley, routine takes over. Women walk toward communal water taps, metal gagri containers balanced with ease born from years of practice. Laughter rises easily here, woven into work. News travels fast: whose crops are ready, whose child has exams, who returned from abroad.

Courtyards are swept clean with straw brooms. Small shrines receive flowers or a dab of red tika. Hands come together briefly in prayer, not as a ceremony but as a habit.

Religion in the village of Nepal is not confined to temples. It lives in kitchens, courtyards, and fields, quiet, practical, and deeply personal.

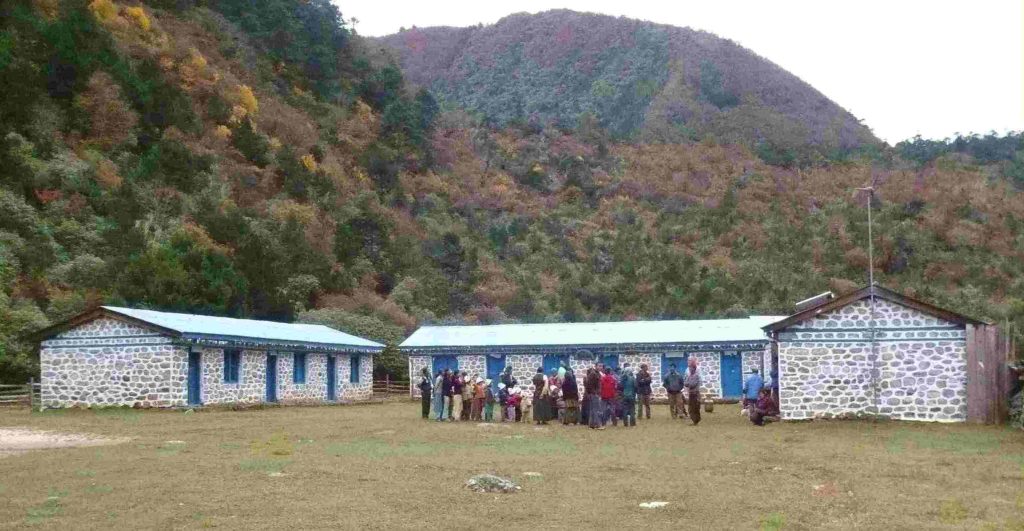

School hours: Young energy on village paths

By mid-morning, the village grows livelier. Children appear in faded uniforms, backpacks slung unevenly over their shoulders. Some walk barefoot along familiar paths, shoes carried until the road turns rough. School may be far, but the walk is simply part of the day.

They move in small groups, laughing, arguing, and making up again within minutes. Education is prized here, even when resources are limited. Parents may not speak openly of dreams, but they carry them quietly, hoping their children will have choices they never did.

To outsiders, the scene feels warm, almost cinematic. But it is built on discipline, expectation, and resilience.

Late morning: The land takes priority

Once children are gone, the village settles into work. Men and women head toward terraced fields, tools resting across their shoulders. Others tend livestock, buffalo, goats, chickens, each animal known individually, each task repeated with care. Farming here is not romantic; it is necessary, physical, and relentless.

Time is measured by progress, not minutes. Fields must be planted before rain arrives, harvested before clouds gather. Paths are repaired after monsoon damage. Work does not pause for convenience.

Neighbours help without being asked. If one family is harvesting, others show up. Tomorrow, the favour will be returned. Cooperation is not optional; it is survival.

Midday: Dal bhat and the pause that follows

By noon, the sun sits high, and kitchens come alive again. Dal Bhat, rice, lentils, seasonal vegetables, and sometimes a small portion of meat, is prepared with practised efficiency. It is not elaborate, but it is deeply satisfying.

Meals are shared, often eaten with hands, and seated close to the ground. There is conversation now about crops, prices, children, politics, and weather. Food here is not rushed. It fuels both body and connection.

After lunch, the village slows. This is the quiet hour. Animals rest. People rest. Even the wind seems to soften. This pause is not laziness; it is wisdom, shaped by climate and labour. Energy is saved for later.

For travellers used to constant motion, this stillness can feel unfamiliar. But it is often here that reflection finds space.

Afternoon: Small commerce and daily negotiations

As the heat eases, activity resumes. Some villagers walk to nearby shops or weekly markets to buy essentials, salt, oil, tea, and soap. Small conversations happen everywhere: prices negotiated, favours exchanged, news updated.

Phones come out now. Messages are checked. Calls are made to family members working in cities or overseas. The modern world is not absent from villages; it is simply absorbed at a careful pace.

Young people gather in shaded areas, talking about work, migration, and opportunities beyond the hills. Many have left before. Many will leave again. The village knows this, accepts it, and prepares for it.

Evening: Community returns home

As the sun dips lower, livestock are brought back to sheds. Smoke rises again from kitchens as dinner preparations begin. Children return from school, shoes dusty, energy intact. Homework is done under fading daylight or a single bulb powered by unreliable electricity.

Neighbours stop by each other’s homes, sometimes without invitation. Tea appears automatically. Conversations stretch easily into laughter.

This is when the village feels most communal. Doors remain open. Voices carry gently across courtyards. The day’s labour loosens into shared presence.

Nightfall: Fires, stories, and quiet reflection

After dinner, families gather close, around a fire in winter, around conversation in warmer months. Elders tell stories of the past: of seasons harsher than this one, of journeys taken on foot, of festivals before roads arrived.

Children listen half-heartedly, half-curiously. They have heard these stories before, yet something about them always stays. The village darkens quickly. Stars appear sharply in skies untouched by city lights. One by one, houses go quiet. There is no rush to sleep, only a natural surrender to night.

What a full day teaches you

Spending a full day in a Nepali village reveals something travellers often miss: life here is not simple, but it is intentional. Tradition bends without breaking. Modernity arrives slowly, negotiated rather than imposed.

Villages are not frozen in time; they are adapting carefully, choosing what to keep and what to change.

When travellers leave, it is rarely the scenery they remember most. It is the rhythm. The way the day held everything, work and rest, effort and connection, silence and laughter, without needing to hurry.

From bells at dawn to fires at dusk, a Nepali village teaches you something quietly profound: a good day does not need to be extraordinary. It only needs to be lived fully, in step with the world around you.